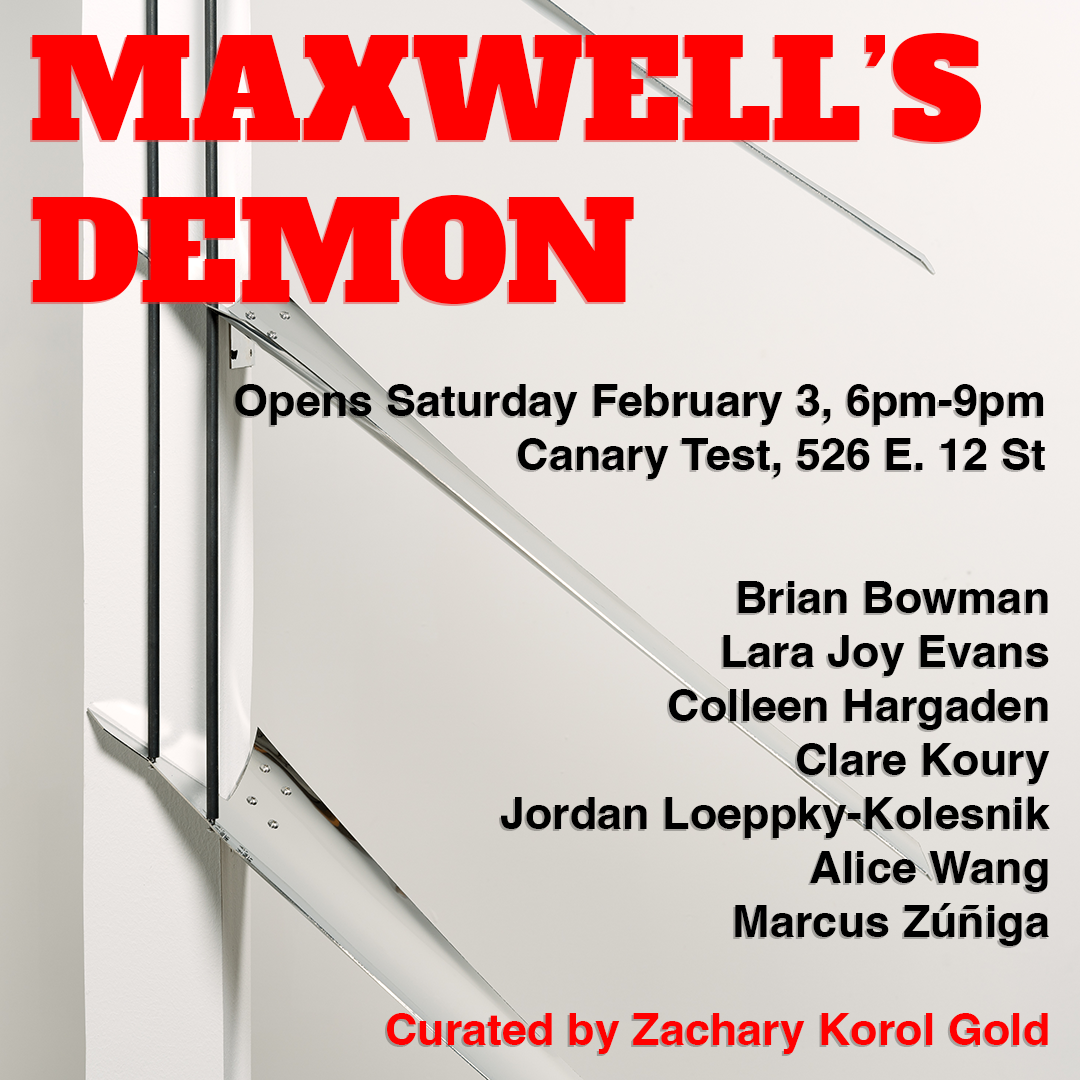

Maxwell's Demon: Opening Reception at the Canary Test

“If we conceive a being whose faculties are so sharpened that he can follow every molecule in its course, such a being, whose attributes are still as essentially finite as our own, would be able to do what is at present impossible to us.” —James Clerk Maxwell, Theory of Heat, 1871

In a letter in 1867 and his 1871 book Theory of Heat, the physicist James Clerk Maxwell imagined an atomic-scale being commanding a tiny massless door between two chambers of gas. Opening or closing the door, it could permit individual molecules to pass in either direction depending on their speed, warming one chamber while cooling the other (see figure below). This thought experiment intended to demonstrate the limits of Lord Kelvin’s second law of thermodynamics, formulated nearly two decades prior, which held that the contact of two systems results in their temperatures finding equilibrium, or, that entropy never decreases. Labeled “demon” by Kelvin, Maxwell’s being of sharpened faculties demonstrates that the second law, which established the irreversibility of entropy and the arrow of time, is not an ontological certainty but a statistical reality.

Set aside as a curious puzzle, the demon reared its head again in 1929, when physicist Leo Szilard used its two chambers of different energies as the model for a new theory that equated negative entropy, or organization, with information, a theory in which intelligence attains thermodynamic properties. Through Szilard, Maxwell’s hypothetical energy difference became the predecessor to the binary digit, a representation of information central to the development of cybernetics and systems theory beginning in the mid-twentieth century.

Returning to Maxwell reveals a hydraulic underpinning of information that contemporary systems logic abstracts. His “neat-fingered being” was a bare point of intelligence, a being who sensed individual energy differences and whose knowledge produced organization. The demon positions the single particle against the fluid mass, the representation of form against the advance of entropy. If our own intelligences contacted atoms directly, we too could sort them, “only we can’t, not being clever enough.”

Maxwell’s error was not attempting to violate Kelvin’s second law, but severing the demon’s intelligence from its embodiment. We, too, organize atoms, but without thinking about it, transmuting our world into flesh, motion, and heat. Through our bodies, we manipulate our worlds into new structures available for contemplation through our faculties of sense, into forms conducting psychic energies. Information is not (only) binary, but rather, arises from a sensuous difference between the particular and the aggregate—a difference of representations of difference, a difference that makes a difference, a différance. In each act of embodiment, composition, and aesthesis, a primordial resistance to entropy.

Here, Brian Bowman stages a rock salvaged from a nuclear mine next to its copy. Lara Joy Evans paints a picture reminiscent of digital and aerospace technologies imagined by, and commanded by, an artificial intelligence model. Colleen Hargaden constructs copper electroculture antennas, tools that connect plants to ambient electric fields to stimulate their growth. Clare Koury fuses layers of metal and earth materials into orgonite, a substance building on the embodied psychoanalysis of Wilhelm Reich. Jordan Loeppky-Kolesnik builds a weir, drawing from the architecture of human-made water dams to control the flow of bodies in space. Alice Wang gilds fossils and an image of a meteor in silver, giving these objects with past lives, living in ancient oceans or gliding through the cosmos, new presence. Marcus Zúñiga hangs a lens, channeling light through its floral form. Each conducts and organizes energies—electromagnetic, nuclear, temporal, social, psychic—through objects, through us.